|

| Conversation partners (from www.arch.tamu.edu/). |

Maybe it’s not that bad. Researchers from Cornell, Harvard and Yale universities and the UK’s University of Essex tested conversation partners in five different situations and found a liking gap between what we think and reality. We regularly underestimate how much our conversation partners like us and enjoy our company.

Conversation Tests

Test 1 had 18 pairs of unacquainted, same-gender participants sit together for a 5-minute conversation with the benefit of icebreaker questions (e.g., Where are you from?).

The participants then answered four questions to measure how much they liked their conversation partners (“I generally liked…” to “I could see myself becoming friends with…”) and four analogous questions to measure how much they thought their conversation partners liked them. Participants also completed scales measuring shyness, narcissism, rejection sensitivity and self-esteem and their demographics.

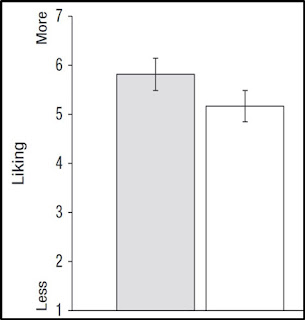

Given that the four measures of how much participants liked their conversation partners were highly correlated, they were averaged into a single measure, actual liking. Similarly, the four highly correlated measures of how much participants thought their conversation partners liked them were also averaged into a single measure, perceived liking.

The test showed that, after a brief conversation, people significantly underestimated how much others liked them. The shyer the participants, the greater their liking gap.

|

| Liking Gap, Test 1, Rating of conversation partners’ actual liking (left) and perceived liking, with 95% confidence interval error bars (from journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0956797618783714). |

Tests 2 and 3 were similar to Test 1 with more participants and no icebreaker questions. Test 2 also asked what thoughts went into forming impressions of their conversation partners, while Test 3 added mixed gender and longer conversations and questions measuring how much the partners enjoyed the conversation.

Participants again underestimated how much others liked them and how much others enjoyed the conversation. Their most salient thoughts about how others viewed them were more negative than their thoughts about how they viewed others. Participants who had longer conversations liked each other more, but the liking gap persisted no matter the length of the conversation.

Test 4 asked 50 pairs of unacquainted conversation partners in “How to Talk to Strangers” workshops how interesting they would find each other, both before and after their conversation. Participants predicted they would find their conversation partner more interesting than their partner would find them to be, and this mistaken belief grew more mistaken after participants had a conversation.

|

| Liking Gap, Test 4, Actual and perceived interesting ratings before (left) and after conversations, with 95% confidence interval error bars (from journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0956797618783714). |

Wrap Up

The study repeatedly found that people systematically underestimate how much their conversation partners like them and enjoy their company. The liking gap persisted after short or long conversations, over the course of a year and whether the participants were students or members of the general public.

People tend to hold themselves in high regard; however, conversation appears to be a domain in which people display uncharacteristic pessimism about their performance. Clearly, conversations are a greater source of happiness than we realize, as others like us more than we think. Thanks for stopping by.

P.S.

Study of conversation liking gap in Psychological Science journal: journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0956797618783714

Article on study on TIME website: time.com/5396598/good-first-impression/

A version of this blog post appeared earlier on www.warrensnotice.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment