Welcome back. Among the interesting studies published during my hiatus was one from researchers with Cambridge and Oxford universities. They found the self-reported mental health and wellbeing of 1 in 3 youths improved during England’s first COVID-19 lockdown.

|

| Self-reported change in mental wellbeing of 16,940 youths during England’s first COVID-19 lockdown (from link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00787-021-01934-z). |

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, mental health challenges were the leading cause of disability and poor life outcomes in young people, with up to 1 in 5 children ages 3 to 17 in the U.S. having a mental, emotional, developmental, or behavioral disorder…

The pandemic added to the pre-existing challenges that America’s youth faced…This Fall, a coalition of the nation’s leading experts in pediatric health declared a national emergency in child and adolescent mental health.

The UK study doesn’t detract from the crisis, it simply adds perspective: not every youth got worse. Determining why one-third fared better might provide insight for promoting youth mental health and wellbeing going forward.

Data for Analysis

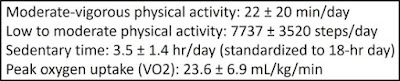

The researchers used data from the OxWell Student Survey, a recurring, cross-sectional, self-report survey relating to mental health and wellbeing. The school-base survey of England’s students, aged 8 to 18, contains questions repeated in each iteration as well as new questions added in response to social and environmental events and emerging research.

For the current study, 16,940 students were surveyed June-July 2020 at the tail end of England’s first national lockdown. They answered questions about their experiences with the pandemic, school, home, lifestyle, relationships and more.

Examining the Data

The study was limited to a descriptive analysis of data, which is probably sufficient to highlight major differences without resorting to statistical testing. Descriptive analysis is also the simplest way for me to summarize key findings from the reported results.

Toward that end, I’ve prepared a table relating the youths’ self-reported changes during the lockdown to the number of those whose mental wellbeing got better, worse or remained the same. I’ve listed 14 items derived from a table the researchers reported with over 100 items. This is not to say the reported detail wasn’t significant; only that it’s well beyond the scope of what I needed to capture some core findings. I encourage you to review the paper to pursue the topic in greater depth.

|

| Relationships of selected variables with self-reported change in mental wellbeing of 16,940 youths during England’s first COVID-19 lockdown (modified from Table 2 of link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00787-021-01934-z). |

The students whose mental wellbeing improved during the lockdown self-reported that they were able to get all the academic help they needed at home, managed school tasks better, were bullied a little less, had better relationships with friends and family, felt less left out and less lonely, and exercised as well as slept more.

Wrap Up

As the researchers point out, the survey showed that students who reported improved mental health and wellbeing were more likely than their peers to report improvement across the full range of school, relational and lifestyle factors.

The impact of lockdown was dependent on a number of factors, such as gender, pre-pandemic mental health, social relationships, school connectedness, online learning experience, family composition and family financial situation.

While the crisis is real, many students did indeed experience improved mental health and wellbeing. Thanks for stopping by.

P.S.

Study of UK students during lockdown in European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry journal: link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00787-021-01934-z

Article on study on EurekAlert! website: www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/944267

U.S. Surgeon General’s advisory: www.hhs.gov/about/news/2021/12/07/us-surgeon-general-issues-advisory-on-youth-mental-health-crisis-further-exposed-by-covid-19-pandemic.html

Oxwell Student Survey and information for parents:

bmjopen.bmj.com/content/11/12/e052717

www.psych.ox.ac.uk/research/schoolmentalhealth/parent-information-sheet-1