Welcome back. When I was very young, the only concern about getting a vaccination was whether the needle would hurt. Maybe it was only my community or city or the limited media coverage. Maybe there was vaccination pushback we didn’t hear about. Anti-science is not some new creation; it’s just gotten out of hand.

|

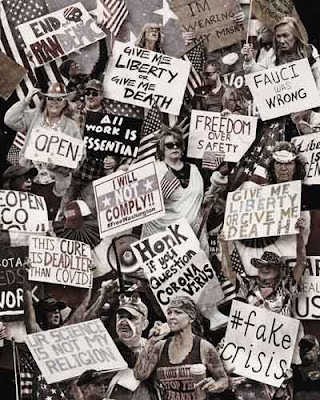

| Scenes from anti-lockdown protests across the U.S. (photo-iIllustration by Eddie Guy from nymag.com/intelligencer/2020/07/republican-response-coronavirus.html). |

Foundations of Anti-Science Beliefs

The researchers reference classic work on persuasion as applying to the rise in people rejecting subjects such as vaccines and climate change.

They describe anti-science beliefs as being built on four foundations or bases:

- Thinking scientific sources lack credibility

- Identifying with groups that have anti-science attitudes

- A scientific message that contradicts a person’s current beliefs

- A mismatch between how a message is presented and a person’s style of thinking.

Each of the four bases reveals what happens when scientific information conflicts with what people already think or their style of thought; each makes it easier to just reject the information.

|

| COVID-19 vaccine protestors (photo by John Lamparski, AP, from www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/08/vaccine-refusers-hesitancy-mandates-fda-delta/619918/). |

The researchers attribute the increase in anti-science attitudes to developments that made it easier to persuade people against scientific consensus.

Social media and a variety of news sources now offer people their own version of the facts.

A related development is the influence of political ideology. Although people always had political views, politics didn’t permeate everything including science and scientific beliefs. Political ideology is now a core part of people’s identity, affecting how they react to politicized scientific evidence such as climate change. Scientific information may be rejected rather than allowed to overturn pre-existing political beliefs.

|

| Climate change has gained acceptance, but Sen. James Inhofe was on the Senate floor, 26 February 2015, using a snowball as evidence that global warming was a hoax (from C-SPAN photo). |

What Can Be Done?

The researchers write that research on attitudes and persuasion shows how to address at least some drivers of anti-science attitudes.

One way they note is to convey messages that show an understanding of other viewpoints. Acknowledge there are valid concerns but explain why the scientific position is preferred. An example they give concerning COVID-19 is to concede that wearing masks can be uncomfortable but explain the discomfort is worth it to prevent the spread of disease.

Another way is to find common ground with those who reject science even if what you have in common has nothing to do with science. Avoid making people feel they’re being attacked or that you’re so different from them as to lack credibility.

In essence, presenting a simple, accurate message may not be enough; it’s how you communicate that message. Psychological research can help scientists learn to present their work to different audiences, including those that might be skeptical.

Wrap Up

The researchers conclude that there’s an opportunity to counteract the anti-science attitudes and sentiment. There are evidence-based strategies to increase public acceptance of science.

I would add the importance of conveying that science is not always correct. In fact, it builds on being wrong, on challenging ideas and changing if new facts emerge toward greater understanding and improved solutions. Thanks for stopping by.

P.S.

Anti-science background: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antiscience

Study of anti-science in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences: www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.2120755119

Article on study on EurekAlert! website: www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/958093

No comments:

Post a Comment